The Genealogy of the Malay Boy

by Tan Yong Jun

This is not an essay about Cheong Soo Pieng per se, but about one of his pictorial motifs and our interactions with it. Naturally, the artist cannot be disassociated from this exploration and, indeed, we need to hold him complicit in our act of viewing. Our focus for now however will not be on the artist but on the life one of his motifs took on, escaping the control of its creator.

It is important to keep in mind that artists do not have a monopoly over the meaning of an artwork. Though the artist’s intention is important, it is not paramount. Art can be perceived and understood even when disassociated from its context. The perception of the viewer and whatever context they bring to the experience intertwines with the artists’ attempts at expressing their ideas, comingling to form meaning. Many suppositions in this essay may not be true to Soo Pieng’s intents, but they explore how one may come to interact with his art and form meanings from these encounters. In a way, this method is essential in studying Soo Pieng; he left us with scant writings and quotations, so the only way we may approach his motives and intents is through necessarily misrepresentative means.

The critique of canonical figures is often uncomfortable, especially when many value systems are entrenched within the perpetration of certain narratives. Soo Pieng is no different. However, I feel that the greatest disservice we can do to an artist is to flatten their practice with a hagiographic approach. Soo Pieng is not a masterpiece machine. He does not turn out flawless paintings one after another which are aesthetically and ideologically without fault. He is a thinking artist, with his own baggage and impulses, a product of his time. He explores his environment and attempts to resolve the tension and contradictions he perceives within through aesthetic means, though naturally falling prey to human limitations and unable to fully reconcile life and art. To me, the idea of a fallible Soo Pieng is much more valuable than an unassailable icon, and as such critique is both helpful and necessary.

Capturing motifs

Any investigation into Cheong Soo Pieng’s subject matter and motifs requires the foregrounding of his sketches. Sketches were the basis of Soo Pieng’s artmaking, a ‘dictionary of images’ which he worked into more formal paintings, as Seah Tzi-Yan put it. This can sometimes take place over a long period of time; sketches completed in the 1950s were regularly reprised in paintings of the 1980s.

Contrasted with the harshness and violence that often emanates from the camera lens at this time, especially when directed by an elite Chinese émigré with primitivist motives, the sketch mediated between reality and the artist’s (often romanticized) eye. For Soo Pieng, the subject matter was expressed instinctively and immediately in aesthetic languages, and in a way depersonalized and made a motif or symbol for the artist’s later use. This is opposed to working from a photograph, where an artist is confronted by the photographed individual whenever the photographic print is used as a visual aid, dehumanized on every occasion their captured image is transferred onto canvas or paper.

Soo Pieng’s ‘dictionary’ was thus compiled in a way that was an aesthetic reaction to his environment rather than a realistic record. In the political climate of the 1950s-60s, this meant that his sketching practice was a concerted effort at locating and forming symbols that were expedient to his painting conditions. Soo Pieng participated in three major exhibitions in this period—the 1951 joint exhibition of Malayan paintings, the 1953 joint exhibition of Balinese paintings, and the 1956 solo exhibition. All three were held at the British Council Gallery, and thus directly linked to the colonial administration’s ‘Malayanisation’ programme. It is no surprise, then, that Soo Pieng’s sketchbooks were populated primarily with the peoples the administration preferred will make up the post-colonial state.

And yet, despite the cosmopolitanism depicted within the sketchbooks, the Chinese, Europeans, and to a lesser extent the Indians that populated Soo Pieng’s world rarely gets transferred onto his paintings.

Soo Pieng’s aesthetic eye is widely cast, but when he settles on subjects to use in formal paintings, it seems that he was much more interested in the idea of Southeast Asian nativism and indigeneity, expressed through the brown skins of the Malays, Borneans, and Balinese. In this, his practice converges with many other artists of his generation.

Soo Pieng’s sketches of were evidently ideologically based, forming aesthetic motifs that he, as an artist rooting himself in geopolitical Malaya, would use in his imagining of a regional culture, a culture he is now implicating himself within. At this point, the Malay Boy enters the picture.

The Malay Boy

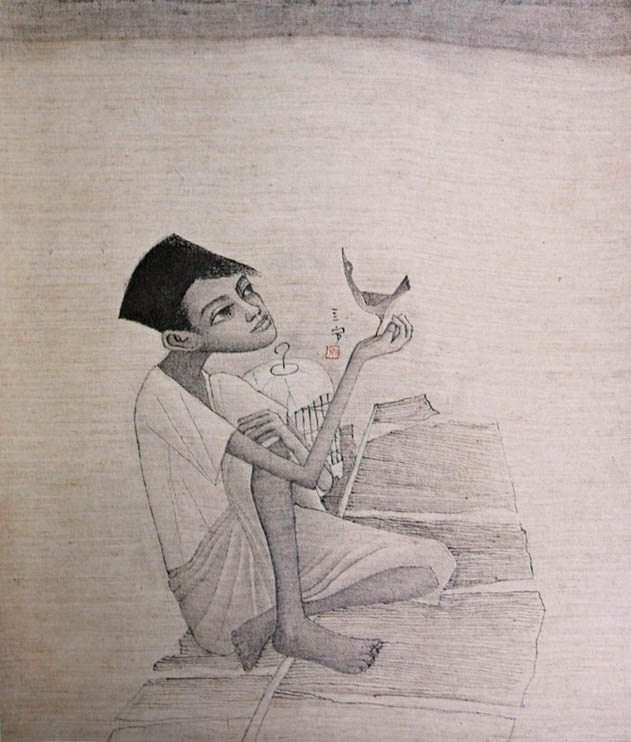

What is referred to as the ‘Malay Boy’ in this essay was identified by Zulkhairi Zulkiflee in a series of works that include Malay Boy (Posterior) (After Cheong Soo Pieng), 2020, a response to Soo Pieng’s painting Malay Boy with Bird![]() , 1953 (fig.1). The titular Boy was presented by Cheong in a bizarre manner—blue-skinned, in a red T-shirt but bare-bottomed, sporting a long and side-parted fringe. The symbol of the Boy’s ethnic identity rests on a songkok. The pivoting posture of the Malay Boy is especially intriguing. He seems at first to face us, who possess a full view of his bare bottoms, but is actually glancing back towards two mynahs, one on his shoulder and another looking directly at his bared bottom. A slight smile suggests that he is either oblivious to or nonchalant about our presence, and corners us into the position of being voyeurs. He is at once readily legible to us as Malay but also entirely surreal.

, 1953 (fig.1). The titular Boy was presented by Cheong in a bizarre manner—blue-skinned, in a red T-shirt but bare-bottomed, sporting a long and side-parted fringe. The symbol of the Boy’s ethnic identity rests on a songkok. The pivoting posture of the Malay Boy is especially intriguing. He seems at first to face us, who possess a full view of his bare bottoms, but is actually glancing back towards two mynahs, one on his shoulder and another looking directly at his bared bottom. A slight smile suggests that he is either oblivious to or nonchalant about our presence, and corners us into the position of being voyeurs. He is at once readily legible to us as Malay but also entirely surreal.

Malay Boy with Bird![]() is iconic of Soo Pieng’s early oeuvre and was a painting I had always known about. I was only spurred to further investigate the motif when Zulkhairi pointed out to me a woodcut, Fruitseller, 1954 (fig.2). If we just look at the Malay Boy paintings individually, the Malay Boy, as a local/native-themed motif developed in the 1950s for Soo Pieng and other Nanyang artists to make sense of their own émigré sense of self, would only stand out as a rather peculiar motif within Soo Pieng’s oeuvre. But when he is contextualised within Soo Pieng’s body of work and with a genealogy of his appearances made clear, we find the Malay Boy’s presence and recurrence emphatically strange.

is iconic of Soo Pieng’s early oeuvre and was a painting I had always known about. I was only spurred to further investigate the motif when Zulkhairi pointed out to me a woodcut, Fruitseller, 1954 (fig.2). If we just look at the Malay Boy paintings individually, the Malay Boy, as a local/native-themed motif developed in the 1950s for Soo Pieng and other Nanyang artists to make sense of their own émigré sense of self, would only stand out as a rather peculiar motif within Soo Pieng’s oeuvre. But when he is contextualised within Soo Pieng’s body of work and with a genealogy of his appearances made clear, we find the Malay Boy’s presence and recurrence emphatically strange.

Fruitseller is not one of Soo Pieng’s more pictorially successful works. It is, in a way, a pastiche of various motifs, including the batik-clad woman hidden by an umbrella. Its value to this discussion lies in how Soo Pieng reused the Malay Boy in a totally different image. Still bare-bottomed, still wearing a songkok, still craning and rotating his neck, the Malay Boy now studies a piece of fruit rather than the unnervingly sentient mynahs. He is caught between three points of gazes, the fruitseller, the dog, and the audience. Within view of others, his bare bottom is particularly stark, especially since the relative sense of scale proves the Malay Boy to be at least a teenager, if not a young adult. If Malay Boy with Bird implies a voyeuristic audience, then Fruitseller presents communal visual assault. The Malay Boy, sans smile, looks to be somewhat aware of his position as a visual object.

![Fig.2. Stills from Proximities depicting Fruitseller by Cheong Soo Pieng found in a classroom.]()

It is within Soo Pieng modus operandi to first capture a scene that perked his interest with a sketch before formalising the subject matter—now a symbol more than an identifiable person—into elements within his paintings. My thoughts thus naturally turned toward his sketchbooks for the excavation of the root image, the initial impression Soo Pieng had of the Malay Boy. This proved futile and, at least for now, we have to be content in

positing the probable existence of a sketch executed around 1951, when Soo Pieng was preparing for the exhibition of Malayan subjects, and that the sketch was probably of a bare-bottomed Malay Boy.

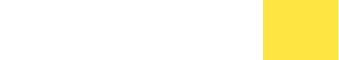

A further look into the published and printer matter of that time turned out to be extremely fruitful. The Malay Boy reappears, twice, in Soo Pieng’s first solo show in Singapore (figs.3 & 4). Their appearance within print matter published by Soo Pieng himself is particularly informative because we can be sure that the titles were given, or at least approved, by the artist. The related publications are both entitled Cheong Soo Pieng (both 1956, Straits Art Commercial Company), one in the form of an artbook with essays, and one as an exhibition brochure with prices. In the book, the painting (fig.3) whose pixelated image seems to give the date of 1951 was named Boy in English and 巫童 (Wutong—Malay Boy) in Chinese. The 1956 painting (fig.4) was more interesting in being named Bird & Boy / 巫人与鸟 (Wuren yu Niao—Malay Person with Bird) in the book and Bird at Rest / 巫人与鸟 in the

catalogue, a subtle but intriguing inconsistency.

![(Left) Fig.3. Cheong Soo Pieng, Boy/巫童, 195(1?), oil on unidentified surface. (Right) Fig.4. Cheong Soo Pieng, Bird & Boy/Bird at Rest/巫人与鸟, 1956, oil on unidentified surface. Scanned images by writer from Cheong Soo Pieng (1956).]()

Since Soo Pieng was not a fluent English speaker and conversed mainly in Hokkien, and since it is the English title that differed for fig.4, it is reasonable to posit that Soo Pieng first titled his paintings in Chinese before translating it to English, with help or not. It is thus the Chinese title that probably holds more clues into thinking about the artist’s intention. In both paintings, the Chinese title emphasises the Malay Boy’s race while the English titles removes this qualifier. Given that the exhibition was held in the British Council Gallery, one cannot help but ruminate on the impact these titles had on an Anglophone/-philic audience. Was the erasure of the racial descriptor because it was self-evident? Unsanitary? Or perhaps just an arbitrary human mistake?

There seems to be little consistency in the translating conventions if there indeed was something totally superfluous or offensive in the racial descriptor to the paintings’ consumers, given that ‘Malay’ appeared in other titles. Was it perhaps some quality specific to the Malay Boy paintings that impelled the translators to drop the racial qualifier, maybe the burning gaze that directly confronts the viewer? I do not pretend to have a resolution to this problem, and indeed it may very well be a problem I have imagined. Looking at these paintings in 2021, however, when we have become acutely aware of the explicit and visible process of ‘othering’ embedded within Soo Pieng’s practice, these omissions are indisputably incongruous and curious, an irresistible wormhole to be encountered when interrogating Soo Pieng’s representation of a Malay subject. Disassociated from Soo Pieng as a person, we rely on his titles (though often posthumously attached) for clues to his painterly

intentions.

Boy features the Malay Boy much as we have previously encountered him, turning back with a songkok, bared bottom, and a mynah on his shoulder. As we can only

encounter him through a black and white reproduction, one is left to wonder whether he is blue or brown. My sense is that Soo Pieng’s featuring of ‘othered’ skin tones as red, black, or (extremely unusually) blue are rare and only surfaced in a short timeframe, and as such I am inclined to believe the Malay Boy is brown in this painting (and perhaps therefore allowing the racial descriptor to be removed from the title).

As opposed to the other iterations of the Malay Boy, who turn toward you but with pupils directed elsewhere, the Malay Boy here stares directly at you. His mouth is hidden by his shoulder, which removes the sense of indifference he exudes in the other paintings. The Malay Boy, along with the mynah perched at the same level, returns your gaze with intent and force, as if daring you to take a prolonged look at his bared bottom. A basket of phallic forms (bananas?) is positioned right at his hip, accentuating the corporeality of his body and the parts clothed and bared. In Boy, the Malay Boy seems to leap out of the artist’s control and, with Soo Pieng’s relatively realist depiction, confront the viewer the way a real person would. As we look into the Malay Boy’s eyes, we become unsettled and acutely aware of our voyeuristic and invasive gaze, perpetrated through canvases and boards.

Bird and Boy/Bird at Rest elicits none of these intense reactions. His image is respectable, benign, even tepid, a perfectly aestheticized subject matter. For first time, we get to see the Malay Boy fully clothed (though we do not preclude other yet uncovered Malay Boy paintings). He squats and opens a coconut, and we see musculature on his calves in place of an impastoed bottom. On his shoulder, ‘resting’ but about to take flight, is the ubiquitous mynah. Here we notice the most peculiar

element of this otherwise relatively sanitised and decorative painting—the Malay Boy’s pupils are painted to take up two-thirds of the eye, pointed towards the Boy’s right, across his shoulder. The illusory effect is that the Malay Boy is, physiologically speaking, looking at the mynah, and yet it is hard for us to believe that he is not indeed gazing back at his audience.

Is this Mona Lisa-like effect simply the artist’s sleight of hand, or perhaps a reflection of our psychological profile? Do we require the subjects of our paintings, especially when their depersonalised functions are to serve as motifs and symbols, to be inert, crystallised, and passive? And is it our fundamental uneasiness in this fragile truce, this relationship between gazer and gazee, that we instinctively react to any hints of a transgression when the subject turns his eyes back onto his audience?

Another point of curiosity emerged in my search for the Malay Boy. Amidst the generic titles of Malay Woman, Malay Family, Malay Life, etc. in the 1956 catalogue, there is an Ahmad/亚末 (Mandarin: Yamo; Hokkien: A-muat). Who is this Ahmad, so singular that Soo Pieng found it necessary to name him within an exhibition that names no other? Might he be Boy (fig.3), pictured in the book but not in the catalogue? It certainly is possible, though I instinctively resisted that rather logical conclusion.

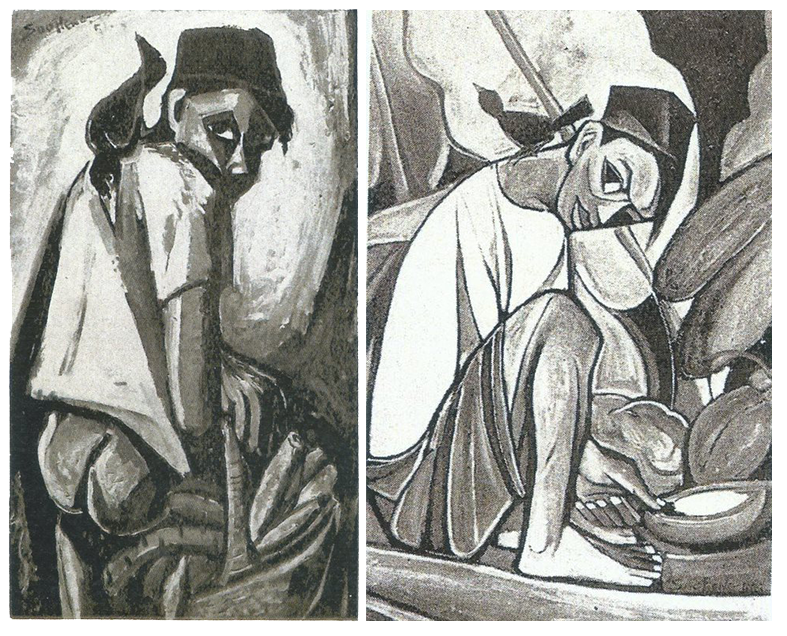

And so, I searched further, and found peeking from within Soo Pieng’s photo albums another Malay Boy (fig.5)![]() . Might he be the elusive Ahmad? This photo was inserted alongside many other photos of artworks produced in the first half of the 1950s, a significant number of which were exhibited in 1956. It is entirely possible that this painting featured in the same exhibition, and thus could plausibly be the painting that bore the now-disembodied title Ahmad/亚末. The subject matter certainly fits the title.

. Might he be the elusive Ahmad? This photo was inserted alongside many other photos of artworks produced in the first half of the 1950s, a significant number of which were exhibited in 1956. It is entirely possible that this painting featured in the same exhibition, and thus could plausibly be the painting that bore the now-disembodied title Ahmad/亚末. The subject matter certainly fits the title.

Sarong-clad and bare-chested, this Malay Boy inverts the sartorial elements we have previously encountered into an image that is logically sound. Holding a coconut with exaggerated hands, he looks at us and smiles, without a sense of subversion, tension, or surreality, simply acknowledging our confelicitous presence as he is about to enjoy his treat.

The birds, pigeons rather than mynahs, are perched on stands and baskets without an unsettling sense of sentience and does not participate in our gaze. The scene is cubistically treated and, most probably, with a fauvist colour sensibility, a modernist depiction of a realist if romanticised Malayan scene.

Going back to the conspicuously absent sketch, we would expect an initial recording of a scene to be the closest to reality, captured on paper with some aesthetic interventions but nothing too surreal. If we accept fig.5 to be an iteration of the Malay Boy rather than an entirely separate subject, then it must be the closest interpretation of the sketch that we are able to access. And no wonder this image, closest to reality, poses the least amount of challenge to the viewer. The Malay Boy takes on an active role, inviting you to witness his snacking and (perhaps) to sketch him. The gaze is met by equals.

Is this Ahmad? It certainly makes sense that Soo Pieng, sketching components of the novel Malayan life around him, might have known this Boy that would feature soheavily in his practice by name. We do not get many

instances of a name being attached to a Soo Pieng

portrait and, when there is one, it is almost always of the elite milieu of Christina Loke or Khoan Sullivan. Zulkhairi raised the point that Ahmad may be a generic term used to refer to Malays at that time, much like the John of Roti John. It certainly is possible, but with my understanding of Soo Pieng, Ahmad is a name, and the Malay Boy, before being trans-(/dis)figured and transposed, was probably Ahmad.

Behind the Easel

I have, of course been speaking about the Malay Boy as if he placed himself in these various settings. What about the artist, who positioned and presented him thus? Why did Soo Pieng find it necessary to capture the image of a Malay boy and invert his dress, divert his gaze, and pervert his identity?

The first question to address is what sort of function the Malay Boy had in Soo Pieng’s paintings. Much (but perhaps still not enough) have been said about the Nanyang painters’ inheritance of Gauguin’s gaze via Le Mayeur, wherein the depiction of indigeneity was an act of ‘othering’, a concerted attempt at differentiating via the painted image between two groups of people living in a certain region. Soo Pieng’s figural paintings, though it cannot be simply characterized in this manner, certainly demonstrate these impulses, with layers of sexualization, primitivism, and cosmopolitanism varnishing his canvas.

Was the Malay Boy just another of Soo Pieng’s many brown-skinned subjects, or a motif with its specific set of particularities? The mind immediately veers towards his Balinese and Bornean (specifically Dayak) Boys. Many of these boys were sketched with a bared bottom, but this was usually with the full nudity that signified juvenile innocence, a symbol diametric to the civility of their painters. Moreover, many of these Boys were part of a group of subjects that has often been broadly identified as ‘mother and child’. Why this pairing so intrigued Soo Pieng is a question for another study, but it stands to reason that the Malay Boy was not simply a subset of a group that included these other Boys. (There is a series of works featuring two Malay boys playing with a bird, and I have considered them separately.)

Should the Malay Boy be grouped together with Soo Pieng’s bare-breasted female figures, then? This comparison seems more convincing and logical but is still found wanting. It has now been widely accepted that the painting of Southeast Asian female nudes by Nanyang painters was a symbolically violent act of representation that erects a power relationship between painter and subject. This argument holds its ground despite the common defence that it is merely the bodily form that was being formalistically studied; we see neither a proliferation of Chinese female nudes nor Southeast Asian male nudes in Nanyang art. Might we understand the Malay Boy’s bizarre and deliberate form of nudity as another form of native emasculation, a modernist Chinese émigré painter’s symbolic subjugation of a juvenile and innocent indigene?

While this is a temptingly neat and tidy conclusion, it does not fit within the reality of Soo Pieng’s practice. For all the endemic faults of Soo Pieng’s generation, Soo Pieng was indeed an artist with genuine curiosity, granularity, and introspection in his observations of Southeast Asia, even as they were co-existent with less desirable impulses. His sketched records of customs and artefacts of both the touristic and everyday varieties display broader and greater sensitivity and parity as compared to other artists of the period, particularly when he focuses on the many forms of art that were then commonly known as ‘applied’—batik, boatmaking, rattan weaving, etc. In a late piece of writing (Sinchew Jit Poh, 1981) we see proof that Soo Pieng’s curiosity did develop into a degree of reflexivity, as he called for indigenous applied arts to become an integral part of ‘true’ Nanyang art. It seems unreasonable, if we accept this reading of Soo Pieng’s painterly character, for him to that deliberately emasculate and violate the Malay Boy, as symbol for the community Soo Pieng was a guest in.

The conclusion must be that there can be no conclusion as this point. We cannot reconcile Soo Pieng’s demonstrated sensitivity and willingness to engage with Southeast Asian cultures and peoples with the calculated and pointed pictorial violence that wrecked the Malay Boy. Ultimately, we are unable to fully understand the significance of the Malay Boy to Soo Pieng’s oeuvre and sense of self. As disclaimed, our intrigues into Soo Pieng’s paintings are severely hampered by a lack of primary material to work on. Perhaps this is the crux of the matter—our perceptions of the Malay Boy, as valid and reasonable as they are, are uncoloured by the artist’s stated motives, and are therefore perceived at a remove from the artist’s intention.

Behind the Frame

Soo Pieng’s oil paintings of his last decade revelled in decorative beauty—their atmosphere baroque, their appearances byzantine. Earlier motifs and subjects were ‘revisited’, in T. K. Sabapathy’s words, and given new meanings, reflecting both Soo Pieng’s personal development and his collectors’ expectations. Amid this flurry of gold paint and elongated limbs, the Malay Boy makes a final appearance, just a few years before Soo Pieng’s death (fig.6).![]()

The (relative) naturalism of the Malay Boy here is starkly contrasted with the Balinese Women of the same period, who had long since been disassociated from their individual identities under layers of aesthetic manipulation. Sporting the iconic songkok that presses down his fringe, this Malay Boy is surely the same person (Ahmad?) we have encountered decades ago.

His pigeon now rests on his palm and entertains him, while he sits on a banana leaf, fully clothed. Fleshed out with chiaroscuro, the Malay Boy does not turn nor acknowledge the audience, gazing intently at the pigeon instead. This is the Malay Boy at his most unconfrontational and therefore unoffensive, expediating our consumption of his image without resisting the sterilisation of his identity.

In the 1950s, when Soo Pieng’s art was most steeped in political meanings, his expressions of the Malay Boy were desirable because they showed the ability of émigré and indigenous Malayans to adopt modernist modes,

whether in aesthetics or politics. These Malay Boys served the mental construction of the post-colonial state, and in some ways the position of the Chinese émigrés within it. His intense gazes were not merely emitted but returned, directly addressing his audience, daring them to acknowledge the full validity of his being. This bite has receded by the mid-1970s. Soo Pieng was now an artist in the fullest meaning, serving an art market and cultural community that he had been instrumental in fostering. His paintings were no longer shown in colonial-inflected exhibition spaces but in local-run galleries and museums. His audiences were newly confident Singaporeans, making fortunes in tandem with the state’s economic policies and spending some of it on cultural trophies.

What better symbol of a state and its elites’ self-confidence than a local artist painting local subjects that

could transact at high prices?

Soo Pieng’s audience at the later part of his career did not require the Malay Boy to question, confront, or interrogate them. The image was there to serve the high priests of the commercial state, who counted both the painter and his subject as full members. Once the Malay Boy had been made legible to the Republic, the tension and contradictions embedded within him subsides and he settles on a banana leaf to admires his companion in leisure, his image given over fully to his new admirers. It is at this point when Soo Pieng’s story ends, as he dies from heart failure in 1983.

But the Malay Boy survives Soo Pieng and continues to interact with a new generation of viewers. In 2022, when the politics of identity has never been more acutely felt, we ask how our individual genealogies and histories entwine with the Malay Boy’s as we meet his gaze. Each of us brings different life experiences to our perception of the Malay Boy, and indeed Zulkhairi’s intervention complicates the narrative with a much-needed point of view—that of a person with an identity congruent to the depicted subject. How will he look at the Malay Boy? How will he acknowledge the Malay Boy’s gaze and return it? How will his interactions differ from ours, whoever we may be? Looking back at the painter with the Malay Boy as his avatar, Zulkhairi opens a new chapter in our understanding of Nanyang art, and the artists implicated with this narrative.